-

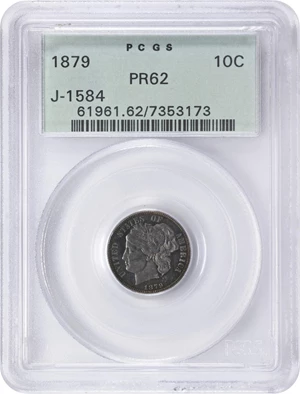

Patterns (1879) Values

Greysheet & Red Book® PRICE GUIDE

Sort by

Legal Disclaimer

The prices listed in our database are intended to be used as an indication only. Users are strongly encouraged to seek multiple sources of pricing before making a final determination of value. CDN Publishing is not responsible for typographical or database-related errors. Your use of this site indicates full acceptance of these terms.

The Greysheet Catalog (GSID) of the Patterns (1879) series of Pattern Coinage in the U.S. Coins contains 153 distinct entries with CPG® values between $1,000.00 and $2,150,000.00.

A panorama of patterns was produced in 1879, highlighted by the misnamed

“Washlady” silver denominations, the elegant “Schoolgirl” silver dollar, and

the $4 gold Stellas in two styles.

Assistant engraver Charles E. Barber’s suite of silver patterns of the dime,

quarter dollar, half dollar, and dollar denominations stands today as among

his finest work. In the late 19th century, this depiction of Liberty was

dubbed the “Washlady” design, a rather unfortunate designation, as the woman

depicted is elegantly coiffed, and certainly not styled as a laundress might

have been. The addition of the ten-cent or dime denomination to these

patterns is quite unusual, as after the Standard Silver series, relatively

few new pattern designs were made of this value.

Beyond the “Washlady” pieces,

a further suite of patterns of the same denomination was made featuring

George T. Morgan’s famous Liberty Head, by now familiar on the regularly

circulating silver dollar, but in combination with a large perched eagle on

the reverse. As engravers are wont to do, Morgan swiped his eagle motif from

an earlier work— essentially the same bird appears on certain gold patterns

of 1878.

Further silver patterns in the series include another dollar portrait

attributed to William Barber (J-1605), and perhaps the most commanding issue

of the year: George T. Morgan’s elegant “Schoolgirl” design. Generations of

pattern enthusiasts have considered this to be one of the very finest pieces

in the entire series. For the obverse, George T. Morgan pictured a

schoolgirl with long flowing tresses, facing to the left, and wearing a

string of pearls. The reverse represents a reappearance of one of Morgan’s

boldest concepts: a defiant eagle facing left, as first used on an 1877

pattern half dollar (J-1512), but deemed to be of sufficient interest that

years later it would be utilized for the reverse of the 1915-S

Panama-Pacific International Exposition commemorative quarter eagle.

Hubbell’s goloid metric alloy furnished the theme for several dollar

patterns in 1879, some of which may have actually been used as true patterns

(for passing around among congressmen and the like), but the situation is

not clear today. Of imposing beauty and simplicity, with a relatively small

portrait surrounded by a large shimmering mirror Proof field, is the new

motif traditionally attributed to George T. Morgan (although Charles Barber

also worked on the die), with Liberty facing left, her hair braided in the

back. This has been called the Coiled Hair style and also was used in

modified form on the rarer type of the $4 of this year.

This brings us to the most famous of all gold patterns: the 1879 $4

“Stella,” so called from the five-pointed star on the reverse of each. Such

coins were the brainchild of the Honorable John A. Kasson, the United States

envoy extraordinary and minister plenipotentiary to Austria-Hungary, who had

earlier served as the chairman of the Committee of Coinage, Weights, and

Measures in Congress. Once again the tired and rejected concept of an

international coinage came to the fore. Then and now, the valuations of

different world monetary units varied with each other, often over a short

span of time. It was Kasson’s thought that a United States $4 coin would be

approximately the same value as the Austrian 8 florins, French 20 francs,

Italian 20 lire, Spanish 20 pesetas, and Dutch 8 florins. The entire idea

was absurd at the start, as approximate values would never satisfy the needs

of commerce, and such pieces would eventually be valued on their gold

content and would not come out in even units of foreign currency.

The current Committee of Coinage, Weights, and Measures, was in favor of the

idea (congressmen then and now often have little acquaintance with the

lessons of history, and act upon the idea of the day) and thought that a

suitable name would be “One Stella,” as a nickname that would go along with

“one eagle,” that being used for the $10 coin, with both the star (as on the

Stella) and the eagle bird (as on the $10) being national emblems. Whether

the star was actually an important American emblem is a matter of question,

but it was important to the committee at the time.

It is thought that assistant engravers Charles E. Barber and George T.

Morgan were each commissioned to devise an obverse design to be shared with

a common reverse, the last featuring the aforementioned five-pointed star

with the inscription ONE STELLA / 400 CENTS incuse, with the mottos E

PLURIBUS UNUM and DEO EST GLORIA surrounding, and with UNITED STATES OF

AMERICA / FOUR DOL. around the border. The DEO EST GLORIA motto must have

been popular with someone at the Mint in this era, for it is also seen on

certain goloid metric dollar patterns.

Barber’s motif featured Liberty facing left, her hair in tresses behind, the

Flowing Hair style as it became known. Morgan’s motif featured Liberty with

her hair in braids, Coiled Hair style. It was announced by someone, perhaps

a Mint official, that 15 of the 1879 Flowing Hair $4 Stellas were struck,

these as patterns, but there was a sufficient demand for them that a few

hundred more were struck for congressmen, who are allowed to acquire them

for $6.50 each. This was an era of great secrecy at the Mint, and virtually

the entire pattern coinage of 1879, including the “Washlady” and Schoolgirl

silver coins, were produced for the private profit of Mint officials. These

were not given to congressmen or openly sold to collectors at the time, and,

indeed, for many issues, their very existence was not disclosed. Collectors

learned of them years later, and at that time were only able to piece

together information as no facts are known to have been recorded. There was

furor concerning the 1879 Flowing Hair Stella, and dealer S.K. Harzfeld, for

one, sought to find out about it. His and other efforts led to certain

pieces being available to the numismatic fraternity. The total number made

is not known, but has been estimated to be 600 to 700, all but 15 of which

are believed to have been struck in calendar year 1880 from the 1879-dated

dies.

With regard to Morgan’s Coiled Hair Stella, this was strictly a delicacy for

Mint officials. None were shown to congressmen, and none were made available

to the numismatic fraternity—the whole matter was hush-hush. How many were

struck is not known, and estimates have ranged from about a dozen up to

perhaps two or three dozen. Whatever

the figure, it is but a tiny fraction of the 1879 Flowing Hair style. In

1880, small numbers of both Flowing Hair and Coiled Hair styles were made

for numismatic purposes and sold privately over a period of time.

Remarkably, it was not until many years later, in The Numismatist

in March 1911, that all four 1879 and 1880 dates and combinations were

illustrated in one place, in “The Stellas of 1879 and 1880,” by Edgar H.

Adams.

As a further consequence of the Kasson proposal for international coinage, a

metric $20 double eagle was proposed. Apparently this also was a numismatic

delicacy, for the motif did not match that suggested by the Committee of

Coinage, Weights, and Measures, and the pieces were made in very small

numbers and privately sold. The obverse depicted Longacre’s standard

portrait similar to that used on the current double eagle, but from a

different hub and also with surrounding inscriptions relating to the metric

system. The reverse was an adaptation of the standard design except with the

motto DEO EST GLORIA instead of IN GOD WE TRUST.

Chief Engraver William Barber died on August 31, 1879. In early 1880 his

son, Charles E. Barber, designer of the Flowing Hair Stella, was named to

the position. Charles was a man of modest talent at best, especially in

comparison to his assistant engraver George T. Morgan (at the Mint since

1876, and capable of doing truly artistic work).

See More See Less

Legal Disclaimer

The prices listed in our database are intended to be used as an indication only. Users are strongly encouraged to seek multiple sources of pricing before making a final determination of value. CDN Publishing is not responsible for typographical or database-related errors. Your use of this site indicates full acceptance of these terms.

Available on Greysheet Marketplace

View All

Auction Ends: 3/26/2026

Auction Ends: 3/26/2026

Auction Ends: 3/26/2026

Auction Ends: 3/26/2026

Dealer Directory

View All Dealers

Greysheet News

View All News

Three-Day Expo Brings Together Dealers, Collectors, and Investors Amid Strong Demand for Rare Coins and Paper Money

Limited, Numbered Hardcover Edition Set to Debut for Author Signatures at the Whitman Spring Coin Expo in Baltimore, March 5, 2026

We are only one month into 2026 and the rare coin market's momentum has continued to surge.

Events

View All Events

Heritage Auctions

Heritage Auctions

Heritage Auctions

Loading more ...

Loading more ...