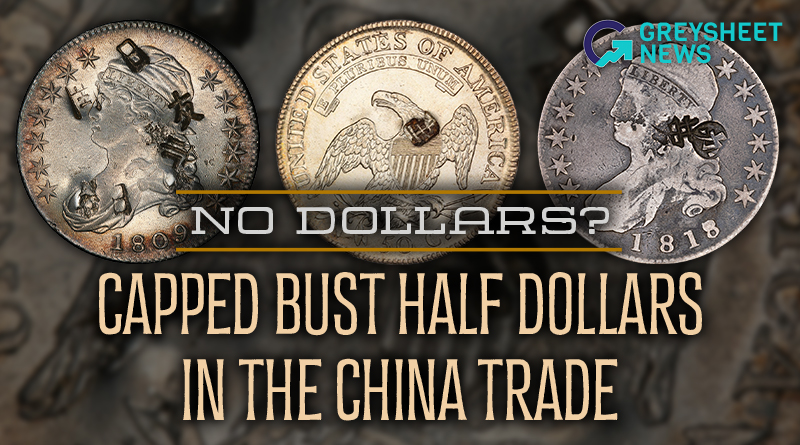

No Dollars? Capped Bust Half Dollars in the China Trade

According to Representative Campbell P. White, in his congressional report of 1832, the exportation of half dollars carried on steadily after 1804 and was extensive from 1811–1821.

by CDN Publishing |

Published on January 28, 2026

Download the Greysheet app for access to pricing, news, events and your subscriptions.

Subscribe to RQ Red Book Quarterly for the industry's most respected pricing and to read more articles just like this.

By Eric Brothers, Contributor

It is known to researchers and hobbyists alike that early U.S. dollars (Flowing Hair and Draped Bust) were employed in the China trade. Such coins, however, were secondary in comparison to the massive amount of Spanish-American dollars exported by U.S. merchants to the Celestial Empire to purchase goods like tea, silk, porcelain, nankeens, and spices. Nonetheless, the vast majority of U.S. silver dollars dated 1794 to 1803 were indeed sent to China in trade.

Export of U.S. Silver Dollars

However, the export of American silver dollars became a problem—a big problem. Very few, if any, dollars were circulating domestically. Bullion dealers and merchants brought Spanish-American dollars to the Philadelphia Mint to turn them into new U.S. dollars—without any seigniorage charge. That was because merchants were trading U.S. dollars in the West Indies for heavier Spanish-American dollars at par. The U.S. dollars had 371.25 grains of fine silver, while the foreign dollars had 373.5 to 374 grains, and even up to 377.25 grains. Then, after having the new U.S. dollars struck, they brought them to the West Indies to trade for more of the Spanish-American dollars. This process resulted in merchants realizing a profit via arbitrage, which drained the U.S. of domestic silver dollars.

Acquiring Spanish-American Dollars

A significant amount of Spanish-American dollars came from Spain’s colonies in the West Indies, where U.S. vessels traded goods for specie. For example, customhouse records from Providence, Rhode Island, document 1,432 ships arriving from the West Indies and South America from 1790 to 1830. They carried dutiable goods such as sugar, coffee, rum, cigars, cotton, molasses, salt, cocoa, mahogany, logwood, indigo, cochineal, and sarsaparilla—and often exchanged them for silver coin. The duties paid on these imports was $2,433,874 during that time, however silver imports were duty-free and often were smuggled in the midst of regional volatility. It would appear that that silver arbitrage occurred during this trade in the West Indies.

End of the U.S. Silver Dollar

The United States silver dollar was a failure. The drain of dollars—due to export and arbitrage in the West Indies—was so extensive that the U.S. Mint suspended their production. That was in 1804 after the completion of striking the 1803 issue. This change was brought about by the presidential administration to halt the export of dollar coins. This new policy was not authorized by any law; mint officers simply stopped minting Draped Bust dollars. The official deathblow of the silver dollar was in 1806, when President Thomas Jefferson formally ended their production.

U.S. Half Dollars Begin to Disappear

One would assume that the silver arbitrage in the West Indies would end, now that the production of silver dollars was over. However, that was not the case. Writes economist J. Laurence Laughlin, "[A]lthough the coinage of the United States silver dollar was discontinued… a profit was still realized by importing Spanish[-American] dollars, because two half-dollars served the same purpose as a dollar piece did before, containing, as they did, as much pure silver as the dollar piece. And our silver continued to be coined and exported." What further evidence do we have of this? According to Representative Campbell P. White, a member of the Select Committee on Coins, in his congressional report of 1832, the exportation of half dollars carried on steadily after 1804 and was extensive from 1811–1821. Let’s explore this further.

Analyzing the Key-Date 1815/2 Half Dollar

The 1815/2 Capped Bust half dollar is considered the key date to the series (1807–1836, Lettered Edge). The research of R.W. Julian has determined that the entire mintage of 1815/2 half dollars (47,150) was paid out to a sole depositor, documented in Mint records as "Jones, Firth, and Co.," a firm that had deposited "nearly $29,000 in Mexican revolutionary dollars on September 18, 1815," per Julian. This Philadelphia merchant firm was the partnership of Isaac Cooper Jones and Thomas Firth. According to the 1846 book, Memoirs and Auto-Biography of Some of the Wealthy Citizens of Philadelphia, Jones and Firth were in the import-export business, "very extensively engaged in the Canton and Calcutta trade."

They turned coinage from revolutionary Mexico—which was poorly received by merchants and shroffs in China—into more recognizable and refined United States coins that would be better accepted in the Orient. At least one 1815/2 half dollar has been found with Chinese chop marks upon it; a photo of it is in John M. Willem’s book, The United States Trade Dollar (1965). When examining the graded populations, we see that PCGS has graded 503, while NGC has graded 286, providing evidence that Jones, Firth, and Co. did not ship all of the 1815/2 half dollars to China. However, it appears that the majority of them were sent there. Due to the rarity of this issue, it is highly likely that these figures include multiple resubmissions—and thus are inflated. This issue was indeed used in domestic commerce. According to Walter Breen, the well-known Economite Hoard of Pennsylvania, "included over 100 examples of the rare 1815/2 overdate—the key date of the series."

Capped Bust Halves in China

W. Taylor Leverage authored only the third book on chopmarked coins in the China trade. He reports that the Capped Bust half dollar series, which debuted in 1807, was used in much of the early U.S. trade with China; that included the prime years of American silver exports. He writes, "Though difficult to locate with chopmarks, the type was certainly the most prevalent American silver coin in Chinese commerce during its years of production [1807–1836]." These coins are not easy to find with chop marks, for the vast majority of American coins sent to East Asia, after being chopped, were melted into Chinese bullion called sycee, which was used as money in China and in the extensive opium trade with British India.

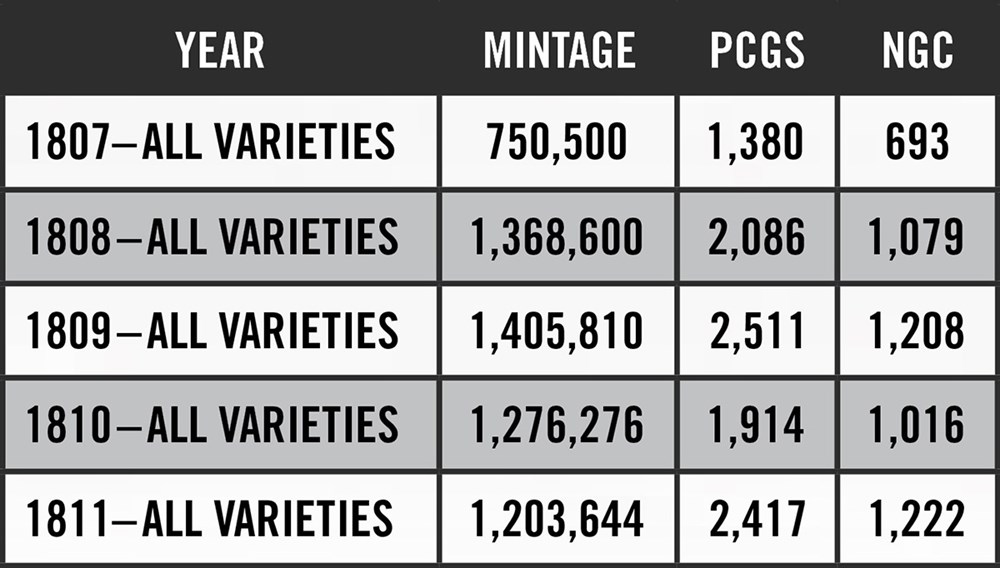

The below table presents circumstantial evidence, suggesting that great numbers of Capped Bust halves indeed ended up in China. Analyzing the number of graded pieces vis-à-vis the original mintage is an interesting method of research, which provides an indication of rarity.

How Much Silver did U.S. Export to China?

Economic and monetary historian Alejandra Irigoin writes, "The United States… after 1785 progressed to become China’s main provider of silver. [The U.S.] accounted for a full 97 percent of silver imports into China between 1807 and 1833." Those years represent almost the entire series of Capped Bust half dollars. The bulk of coins exported during that time were mostly Spanish-American dollars, however it also included significant amounts of Capped Bust half dollars. This is confirmed by White’s report, in which he stated that since opening in 1793 the Mint has coined about $37 million in gold and silver, "of which amount four fifths had probably been exported, leaving only 7–8 million in the United States…"

Further Evidence of Export of Half Dollars

Laughlin writes, "that of $11,000,000 of silver coined in the five years preceding 1831, $8,000,000 had been coined from foreign dollars; and, of the [silver] specie in the United States Bank, only $2,000,000 out of $11,000,000 were in our own coins." This points to extensive exportation of half dollars. In White’s report it states, "it is the peculiarity of our moneyed system [that]…the precious metals are excluded from the minor channels of circulation by a small paper currency…[and] the greater portion of these metals is accumulated in masses at the points of most convenient exportation." Again, this signifies extensive export of fifty-cent pieces. However, it is impossible to quantify the amount of half dollars that were sent to the Celestial Empire.

The 1832 report estimates $5–$8 million of silver in circulation, primarily in half dollars. However, the grand total of half dollars struck from 1807 to 1832 is 58,824,111. The larger estimate of $8 million of silver in circulation represents 27.2 percent of the grand total. So where did the rest of those half dollars go?

The same report presents exports of "American coins"—virtually all being half dollars:

1827, American coins exported, – $1,043,600

1828, do., – [$]693,000

1829, do., – [$]612,900

… [total $]2,349,500

Average annual export, $783,167.

After the Coinage Act of 1834 took effect, silver coins were undervalued, which resulted in their continued exportation. Irigoin writes that after 1834, "Silver coinage then resumed, but U.S. silver coins flowed out of the country…" November 8 of that year saw Niles Weekly Registry report that half dollars were being sold at a one percent premium for export.

However, not all Capped Bust halves were exported to China. The early 1800s saw half dollars imported by Canadian banks and used extensively in Upper and Lower Canada. Workers on the Rideau Canal were paid with Capped Bust half dollars. The Canal was built from 1826 to 1832 and linked the Ottawa River in Ottawa with the Cataraqui River and Lake Ontario at Kingston, Ontario.

Fascinating History, Difficult to Collect

The story of Capped Bust half dollars in the China trade is a captivating one, however a challenging one for collectors. There are very few of that series available with chop marks upon them to collect. Specialists who collect chop marked coins rarely have more than one example. Readers may wonder why there are a good number of chopped U.S. Trade dollars and so few chopped Bust halves. That is because the Trade dollar circulated extensively in China and Hong Kong and became an integral element of East Asian commerce. On the other hand, the Capped Bust half dollar was used to supplement Spanish-American dollars and were mostly melted down and made into sycee bullion.

Sources:

Eric Brothers. "Alexander Hamilton and the Problems with Early American Coinage." ANS Magazine 2023: 4.

Alexandra Irigoin. "The End of a Silver Era: The Consequences of the Breakdown of the Spanish Peso Standard in China and the United States, 1780s–1850s." Journal of World History 20, no. 2 (2009).

W. Taylor Leverage. By Weight, Not by Coyne: An Introduction to Chopmarked Coins. Independently published, 2023.

James Powell. A History of the Canadian Dollar. Bank of Canada. 2005.

Campbell P. White. "Gold and Silver Coins." March 17, 1832. 22nd Congress. 1st Session. Report No. 42.

John M. Willem. The United States Trade Dollar. America’s Only Unwanted, Unhonored Coin. Whitman Publishing Co., Racine, Wisconsin, 1965 (1959).

"Famous 1815/2 Half Dollar Key: The William F. Dunham Specimen." The D. Brent Pogue Collection. Masterpieces of United States Coinage, Part II. September 30, 2015. New York City. Stack’s Bowers Galleries—Sotheby’s.

"United States Custom House Records, Providence," Rhode Island Historical Society (RIHS), Providence, RI. United States Custom House Records, Providence (Record Group 36, held by the RIHS Manuscripts Division, MSS 28, Subgroup 1). https://www.rihs.org/mssinv/MSS028sg1.htm

![Is Kevin Lipton the Most Famous Coin Dealer You've Never Heard of? [Video]](https://images.greysheet.com/l/blogs/20251210/104c7fc4-70d1-41ed-9142-3b2e91fba114.jpg)

Please sign in or register to leave a comment.

Your identity will be restricted to first name/last initial, or a user ID you create.

Comment